Loyalist Clip Art Battle of New Orleans in 1815 Clip Art

"America guided by wisdom An allegorical representation of the United States depicting their independence and prosperity," 1815. Library of Congress.

*The American Yawp is an evolving, collaborative text. Please click hither to improve this chapter.*

- I. Introduction

- II. Free and Enslaved Black Americans and the Claiming to Slavery

- Iii. Jeffersonian Republicanism

- Four. Jefferson as President

- V. Native American Ability and the U.s.a.

- VI. The War of 1812

- VII. Conclusion

- VIII. Primary Sources

- IX. Reference Material

I. Introduction

Thomas Jefferson's electoral victory over John Adams—and the larger victory of the Autonomous-Republicans over the Federalists—was merely one of many changes in the early republic. Some, similar Jefferson's victory, were accomplished peacefully, and others violently. The wealthy and the powerful, middling and poor whites, Native Americans, costless and enslaved African Americans, influential and poor women: all demanded a voice in the new nation that Thomas Paine called an "asylum" for freedom.ane All would, in their own manner, lay claim to the liberty and equality promised, if non fully realized, by the Revolution.

Two. Gratuitous and Enslaved Black Americans and the Challenge to Slavery

Led past the enslaved human Gabriel, close to ane grand enslaved men planned to terminate slavery in Virginia by attacking Richmond in belatedly Baronial 1800. Some of the conspirators would set up diversionary fires in the city's warehouse district. Others would set on Richmond'southward white residents, seize weapons, and capture Virginia governor James Monroe. On August 30, 2 enslaved men revealed the plot to their enslaver, who notified government. Faced with bad conditions, Gabriel and other leaders postponed the attack until the next nighttime, giving Governor Monroe and the militia time to capture the conspirators. Afterward briefly escaping, Gabriel was seized, tried, and hanged forth with twenty-5 others. Their executions sent the message that others would be punished if they challenged slavery. After, the Virginia government increased restrictions on costless people of color.

Gabriel's Rebellion, as the plot came to be known, taught Virginia'due south white residents several lessons. First, it suggested that enslaved Black Virginians were capable of preparing and carrying out a sophisticated and vehement revolution—undermining white supremacist assumptions most the inherent intellectual inferiority of Black people. Furthermore, it demonstrated that white efforts to suppress news of other slave revolts—especially the 1791 slave rebellion in Haiti—had failed. Not only did some literate enslaved people read accounts of the successful attack in Virginia's newspapers, but others as well heard nearly the rebellion immediate when slaveholding refugees from Haiti arrived in Virginia with their enslaved laborers after July 1793.

The Haitian Revolution (1791–1804) inspired gratuitous and enslaved Blackness Americans, and terrified white Americans. Port cities in the United States were flooded with news and refugees. Costless people of color embraced the revolution, understanding it as a call for full abolitionism and the rights of citizenship denied in the Us. Over the next several decades, Black Americans continually looked to Haiti as an inspiration in their struggle for freedom. For example, in 1829 David Walker, a Black abolitionist in Boston, wrote an Appeal that called for resistance to slavery and racism. Walker called Haiti the "glory of the blacks and terror of the tyrants" and said that Haitians, "according to their word, are bound to protect and condolement u.s.a.." Republic of haiti also proved that, given equal opportunities, people of colour could achieve as much as white people.two In 1826 the third college graduate of color in the The states, John Russwurm, gave a commencement address at Bowdoin College, noting that, "Haytiens have adopted the republican form of government . . . [and] in no state are the rights and privileges of citizens and foreigners more respected, and crimes less frequent."3 In 1838 the Colored American, an early Black paper, professed that "no one who reads, with an unprejudiced listen, the history of Hayti . . . can doubtfulness the capacity of colored men, nor the propriety of removing all their disabilities."4 Haiti, and the activism it inspired, sent the message that enslaved and free Black people could non be omitted from conversations nigh the meaning of freedom and equality. Their words and actions—on plantations, streets, and the printed page—left an indelible marker on early national political culture.

The Black activism inspired by Haiti's revolution was and then powerful that anxious white leaders scrambled to use the violence of the Haitian revolt to reinforce white supremacy and pro-slavery views by limiting the social and political lives of people of color. White publications mocked Blackness Americans equally buffoons, ridiculing calls for abolition and equal rights. The nearly (in)famous of these, the "Bobalition" broadsides, published in Boston in the 1810s, crudely caricatured African Americans. Widely distributed materials like these became the basis for racist ideas that thrived in the nineteenth century. But such ridicule also implied that Black Americans' presence in the political conversation was significant enough to require it. The demand to reinforce such an obvious divergence betwixt whiteness and blackness implied that the differences might non be so obvious after all.

The idea and prototype of Black Haitian revolutionaries sent shock waves throughout white America. That Blackness people, enslaved and free, might turn violent against white people, and so obvious in this image where a Black soldier holds up the caput of a white soldier, remained a serious fear in the hearts and minds of white Southerners throughout the antebellum period. January Suchodolski, Battle at San Domingo, 1845. Wikimedia.

Henry Moss, an enslaved man in Virginia, became arguably the nigh famous Black man of the day when white spots appeared on his trunk in 1792, turning him visibly white within 3 years. Equally his skin inverse, Moss marketed himself as "a great marvel" in Philadelphia and presently earned enough money to purchase his freedom. He met the great scientists of the era—including Samuel Stanhope Smith and Dr. Benjamin Rush—who joyously deemed Moss to exist living proof of their theory that "the Blackness Colour (equally it is called) of the Negroes is derived from the leprosy."five Something, somehow, was "curing" Moss of his black. In the whitening body of slave-turned-patriot-turned-curiosity, many Americans fostered ideas of race that would crusade major bug in the years ahead.

The first decades of the new American republic coincided with a radical shift in understandings of race. Politically and culturally, Enlightenment thinking fostered beliefs in common humanity, the possibility of societal progress, the remaking of oneself, and the importance of i's social and ecological environs—a iv-pronged revolt against the hierarchies of the Old World. Notwithstanding a tension arose due to Enlightenment thinkers' desire to classify and order the natural globe. Carolus Linnaeus, Comte de Buffon, Johann Friedrich Blumenbach, and others created connections between race and place as they divided the racial "types" of the globe according to skin colour, cranial measurements, and hair. They claimed that years under the hot dominicus and tropical climate of Africa darkened the skin and reconfigured the skulls of the African race, whereas the cold northern latitudes of Europe molded and sustained the "Caucasian" race. The environments endowed both races with respective characteristics, which accounted for differences in humankind tracing dorsum to a common ancestry. A universal human nature, therefore, housed not fundamental differences but rather the "civilized" and the "archaic"—2 poles on a scale of social progress.

Informed by European anthropology and republican optimism, Americans confronted their own uniquely problematic racial landscape. In 1787, Samuel Stanhope Smith published his treatise Essay on the Causes of the Diversity of Complexion and Figure in the Man Species, which further articulated the theory of racial alter and suggested that improving the social environs would tap into the innate equality of humankind and dramatically uplift nonwhite races. The proper society, he and others believed, could gradually "whiten" men the way nature spontaneously chose to whiten Henry Moss. Thomas Jefferson disagreed. While Jefferson thought Native Americans could improve and become "civilized," he alleged in his Notes on the State of Virginia (1784) that Black people were incapable of mental improvement and that they might even have a carve up ancestry—a theory known as polygenesis, or multiple creations. His conventionalities in polygenesis was less to justify slavery—enslavers universally rejected the theory as antibiblical and thus a threat to their primary instrument of justification, the Bible—and more to justify schemes for a white America, such as the programme to gradually transport freed Blackness people to Africa. Many Americans believed nature had made the white and Black races too dissimilar to peacefully coexist, and they viewed African colonization equally the solution to America's racial trouble.

Jefferson'due south Notes on the State of Virginia sparked considerable backlash from antislavery and Black communities. The celebrated Blackness surveyor Benjamin Banneker, for example, immediately wrote to Jefferson and demanded he "eradicate that railroad train of cool and false ideas" and instead cover the belief that we are "all of i flesh" and with "yet sensations and endowed . . . with the same faculties."6 Many years later, in his Appeal to the Colored Citizens of the World (1829), David Walker channeled decades of Black protestation, simultaneously denouncing the moral rot of slavery and racism while praising the inner strength of the race.

Jefferson had his defenders. White men such equally Charles Caldwell and Samuel George Morton hardened Jefferson's skepticism, offer a "biological" example for Blackness and white people non only having separate creations just really existence different species, a position increasingly articulated throughout the antebellum period. Few Americans subscribed wholesale to such theories, only many shared beliefs in white supremacy. As the decades passed, White Americans were forced to acknowledge that if the Black population was indeed whitening, it resulted from sexual violence and not the environment. The sense of inspiration and wonder that followed Henry Moss in the 1790s would take been incommunicable just a generation later on.

Iii. Jeffersonian Republicanism

Complimentary and enslaved Black Americans were not lone in pushing against political hierarchies. Jefferson'due south ballot to the presidency in 1800 represented a victory for non-elite white Americans in their bid to assume more direct control over the authorities. Elites had made no secret of their hostility toward the direct control of authorities by the people. In both individual correspondence and published works, many of the nation's founders argued that pure democracy would pb to anarchy. Massachusetts Federalist Fisher Ames spoke for many of his colleagues when he lamented the dangers that democracy posed considering it depended on public opinion, which "shifts with every current of caprice." Jefferson'southward ballot, for Federalists like Ames, heralded a slide "down into the mire of a commonwealth."7

Indeed, many political leaders and non-elite citizens believed Jefferson embraced the politics of the masses. "In a government like ours it is the duty of the Principal-magistrate . . . to unite in himself the confidence of the whole people," Jefferson wrote in 1810.8 Nine years later, looking back on his monumental election, Jefferson again linked his triumph to the political engagement of ordinary citizens: "The revolution of 1800 . . . was as existent a revolution in the principles of our government as that of 76 was in it's form," he wrote, "not effected indeed by the sword . . . but by the rational and peaceable musical instrument of reform, the suffrage [voting] of the people."nine Jefferson desired to convince Americans, and the world, that a regime that answered directly to the people would lead to lasting national matrimony, not anarchic segmentation. He wanted to evidence that free people could govern themselves democratically.

Jefferson fix out to differentiate his administration from the Federalists. He defined American union by the voluntary bonds of young man citizens toward one some other and toward the government. In contrast, the Federalists supposedly imagined a union defined by expansive state power and public submission to the rule of aristocratic elites. For Jefferson, the American nation drew its "free energy" and its strength from the "confidence" of a "reasonable" and "rational" people.

Democratic-Republican celebrations frequently credited Jefferson with saving the nation's republican principles. In a move that enraged Federalists, they used the image of George Washington, who had passed away in 1799, linking the republican virtue Washington epitomized to the democratic liberty Jefferson championed. Leaving behind the military pomp of power-obsessed Federalists, Autonomous-Republicans had peacefully elected the scribe of national independence, the philosopher-patriot who had battled tyranny with his pen, not with a sword or a gun.

The celebrations of Jefferson's presidency and the defeat of the Federalists expressed many citizens' willingness to affirm greater direct control over the government as citizens. The definition of citizenship was changing. Early American national identity was coded masculine, just as it was coded white and wealthy; yet, since the Revolution, women had repeatedly called for a place in the conversation. Mercy Otis Warren was 1 of the most noteworthy female contributors to the public ratification debate over the Constitution of 1787 and 1788, but women all over the state were urged to participate in the discussion over the Constitution. "It is the duty of the American ladies, in a particular manner, to interest themselves in the success of the measures that are now pursuing by the Federal Convention for the happiness of America," a Philadelphia essayist announced. "They can retain their rank as rational beings only in a free government. In a monarchy . . . they will be considered as valuable members of a gild, only in proportion as they are capable of being mothers for soldiers, who are the pillars of crowned heads."10 American women were more than mothers to soldiers; they were mothers to freedom.

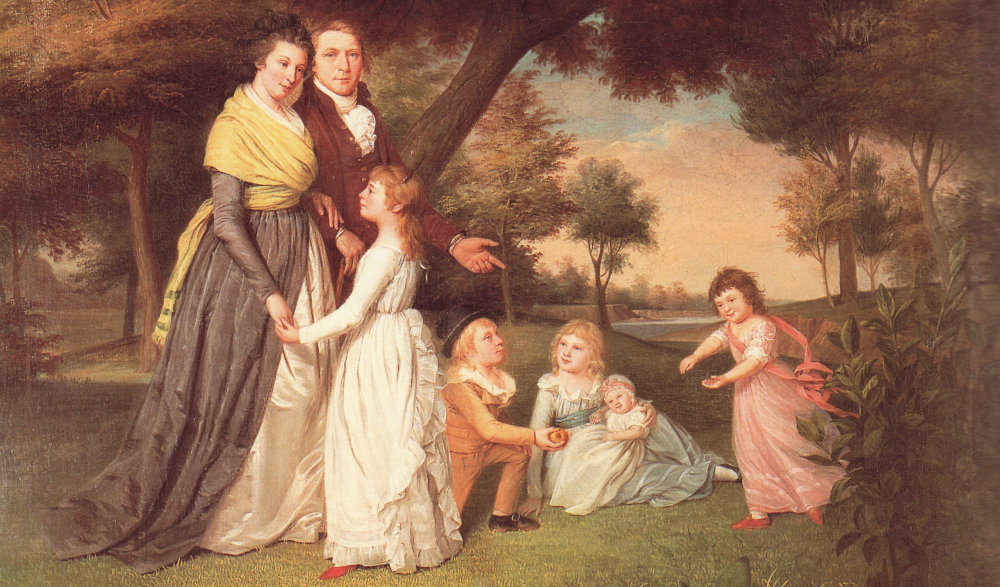

The creative person James Peale painted this portrait of his wife Mary and five of their eventual six children. Peale and others represented women as responsible for the wellness of the republic through their roles every bit wives equally mothers. Historians phone call this view of women Republican Motherhood. Wikimedia.

Historians have used the term Republican Motherhood to describe the early American belief that women were essential in nurturing the principles of liberty in the citizenry. Women would pass along important values of independence and virtue to their children, ensuring that each generation cherished the same values of the American Revolution. Because of these ideas, women'southward actions became politicized. Some even described women's choice of sexual partner as crucial to the health and well-beingness of both the party and the nation. "The fair Daughters of America" should "never disgrace themselves by giving their easily in marriage to any only real republicans," a group of New Jersey Democratic-Republicans asserted. A Philadelphia newspaper toasted "The fair Daughters of Columbia. May their smiles be the reward of Republicans just."11 Though unmistakably steeped in the gendered assumptions most female sexuality and domesticity that denied women an equal share of the political rights men enjoyed, these statements also conceded the pivotal office women played equally active participants in partisan politics.12

IV. Jefferson as President

Buttressed by robust public support, Jefferson sought to implement policies that reflected his own political ideology. He worked to reduce taxes and cut the government'south upkeep, believing that this would aggrandize the economic opportunities of free Americans. His cuts included national defense, and Jefferson restricted the regular ground forces to 3 thousand men. England may accept needed taxes and debt to back up its war machine empire, but Jefferson was adamant to live in peace—and that conventionalities led him to reduce America's national debt while getting rid of all internal taxes during his commencement term. In a motility that became the crowning achievement of his presidency, Jefferson authorized the acquisition of Louisiana from French republic in 1803 in what is considered the largest real manor deal in American history. France had ceded Louisiana to Spain in exchange for Due west Florida later the Vii Years' War decades before. Jefferson was concerned about American admission to New Orleans, which served every bit an important port for western farmers. His worries multiplied when the French secretly reacquired Louisiana in 1800. Spain remained in Louisiana for two more than years while the U.S. government minister to France, Robert R. Livingston, tried to strike a compromise. Fortunately for the United states, the pressures of war in Europe and the slave coup in Republic of haiti forced Napoleon to rethink his vast North American holdings. Rebellious enslaved people coupled with a xanthous fever outbreak in Haiti defeated French forces, stripping Napoleon of his ability to control Haiti (the dwelling of profitable carbohydrate plantations). Deciding to cut his losses, Napoleon offered to sell the entire Louisiana Territory for $xv million—roughly equivalent to $250 million today. Negotiations betwixt Livingston and Napoleon'southward foreign government minister, Talleyrand, succeeded more spectacularly than either Jefferson or Livingston could take imagined.

Jefferson made an enquiry to his cabinet regarding the constitutionality of the Louisiana Purchase, but he believed he was obliged to operate outside the strict limitations of the Constitution if the good of the nation was at stake, as his ultimate responsibility was to the American people. Jefferson felt he should be able to "throw himself on the justice of his country" when he facilitated the interests of the very people he served.13

Jefferson's strange policy, particularly the Embargo Deed of 1807, elicited the most outrage from his Federalist critics. As Napoleon Bonaparte's armies moved beyond Europe, Jefferson wrote to a European friend that he was glad that God had "divided the dry out lands of your hemisphere from the dry lands of ours, and said 'hither, at least, be there peace.'"14 Unfortunately, the Atlantic Ocean soon became the site of Jefferson'southward greatest foreign policy exam, as England, France, and Spain refused to respect American ships' neutrality. The greatest offenses came from the British, who resumed the policy of impressment, seizing thousands of American sailors and forcing them to fight for the British navy.

Many Americans called for war when the British attacked the USS Chesapeake in 1807. The president, nevertheless, decided on a policy of "peaceable coercion" and Congress agreed. Under the Embargo Deed of 1807, American ports were closed to all foreign merchandise in hopes of avoiding war. Jefferson hoped that an embargo would force European nations to respect American neutrality. Historians disagree over the wisdom of peaceable coercion. At first, withholding commerce rather than declaring war appeared to exist the ultimate means of nonviolent disharmonize resolution. In practice, the embargo injure the U.S. economy. Even Jefferson's personal finances suffered. When Americans resorted to smuggling their goods out of the country, Jefferson expanded governmental powers to try to enforce their compliance, leading some to label him a "tyrant."

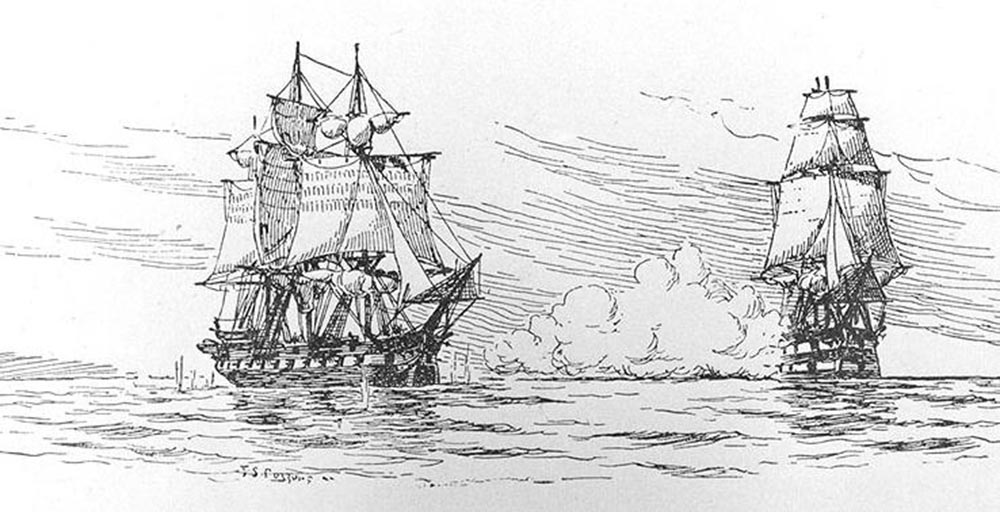

The set on of the Chesapeake acquired such furor in the hearts of Americans that even eighty years afterward the incident, an creative person sketched this drawing of the outcome. Fred S. Cozzens, The incident between HMS "Leopard" and USS "Chesapeake" that sparked the Chesapeake-Leopard Affair, 1897. Wikimedia.

Criticism of Jefferson's policies reflected the aforementioned rhetoric his supporters had used earlier against Adams and the Federalists. Federalists attacked the American Philosophical Society and the study of natural history, believing both to be also saturated with Autonomous-Republicans. Some Federalists lamented the alleged decline of educational standards for children. Moreover, James Callender published accusations (that were later proven credible by Deoxyribonucleic acid prove) that Jefferson was involved in a sexual relationship with Sally Hemings, 1 of his enslaved laborers.15 Callender referred to Jefferson equally "our little mulatto president," suggesting that sex with an enslaved person had somehow compromised Jefferson's racial integrity.16 Callender'south accusation joined previous Federalist attacks on Jefferson's racial politics, including a scathing pamphlet written by South Carolinian William Loughton Smith in 1796 that described the principles of Jeffersonian commonwealth as the first of a glace slope to dangerous racial equality.17

Arguments lamenting the democratization of America were far less effective than those that borrowed from democratic language and alleged that Jefferson's deportment undermined the sovereignty of the people. When Federalists attacked Jefferson, they ofttimes defendant him of acting confronting the interests of the very public he claimed to serve. This tactic represented a pivotal development. As the Federalists scrambled to stay politically relevant, information technology became apparent that their ideology—rooted in eighteenth-century notions of virtue, paternalistic rule by wealthy elite, and the deference of ordinary citizens to an aristocracy of merit—was no longer tenable. The Federalists' adoption of republican political rhetoric signaled a new political landscape in which both parties embraced the straight interest of the citizenry. The Democratic-Republican Political party rose to power on the promise to expand voting and promote a more direct link betwixt political leaders and the electorate. The American populace continued to demand more than direct admission to political power. Jefferson, James Madison, and James Monroe sought to expand voting through policies that made it easier for Americans to purchase country. Under their leadership, seven new states entered the Spousal relationship. Past 1824, only three states nonetheless had rules about how much property someone had to own before he could vote. Never once again would the Federalists regain dominance over either Congress or the presidency; the last Federalist to run for president, Rufus Male monarch, lost to Monroe in 1816.

V. Native American Power and the United States

The Jeffersonian rhetoric of equality contrasted harshly with the reality of a nation stratified along the lines of gender, class, race, and ethnicity. Diplomatic relations between Native Americans and local, country, and national governments offer a dramatic instance of the dangers of those inequalities. Prior to the Revolution, many Native American nations had balanced a fragile diplomacy between European empires, which scholars have called the Play-off System.18 Moreover, in many parts of North America, Indigenous peoples dominated social relations.

Americans pushed for more state in all their interactions with Native diplomats and leaders. Just boundaries were only one source of tension. Merchandise, criminal jurisdiction, roads, the auction of liquor, and alliances were besides key negotiating points. Despite their role in fighting on both sides, Native American negotiators were not included in the diplomatic negotiations that ended the Revolutionary State of war. Unsurprisingly, the final document omitted concessions for Native allies. Fifty-fifty as Native peoples proved vital trading partners, scouts, and allies against hostile nations, they were often condemned by white settlers and government officials every bit "savages." White ridicule of Indigenous practices and disregard for Indigenous nations' belongings rights and sovereignty prompted some Indigenous peoples to turn away from white practices.

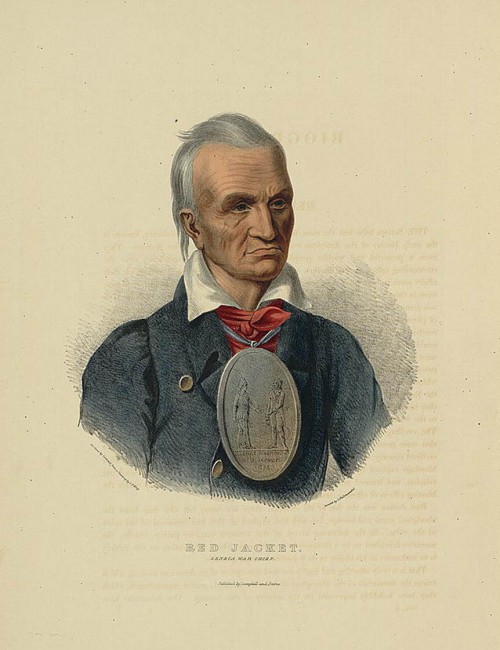

In the wake of the American Revolution, Native American diplomats developed relationships with the United states, maintained or ceased relations with the British Empire (or with Spain in the South), and negotiated their human relationship with other Native nations. Formal diplomatic negotiations included Native rituals to reestablish relationships and open up communication. Treaty conferences took place in Native towns, at neutral sites in borderlands, and in state and federal capitals. While chiefs were politically important, skilled orators, such equally Red Jacket, equally well as intermediaries, and interpreters also played key roles in negotiations. Native American orators were known for metaphorical linguistic communication, command of an audience, and compelling voice and gestures.

.

Shown in this portrait as a refined admirer, Ruddy Jacket proved to be one of the most effective middlemen between Native Americans and U.S. officials. The medal worn around his neck, apparently given to him by George Washington, reflects his position as an intermediary. Campbell & Burns, Red Jacket. Seneca state of war chief, Philadelphia: C. Hullmandel, 1838. Library of Congress.

Throughout the early republic, diplomacy was preferred to war. Violence and warfare carried enormous costs for all parties—in lives, money, trade disruptions, and reputation. Affairs immune parties to air their grievances, negotiate their relationships, and minimize violence. Violent conflicts arose when affairs failed.

Native affairs testified to the complexity of Indigenous cultures and their function in shaping the politics and policy of American communities, states, and the federal regime. Yet white attitudes, words, and policies frequently relegated Native peoples to the literal and figurative margins equally "ignorant savages." Poor treatment similar this inspired hostility and calls for alliances from leaders of distinct Native nations, including the Shawnee leader Tecumseh.

Tecumseh and his brother, Tenskwatawa, the Prophet, helped envision an brotherhood of North America's Ethnic populations to halt the encroachments of the United states. They created towns in nowadays-day Indiana, first at Greenville, then at Prophetstown, in disobedience of the Treaty of Greenville (1795). Tecumseh traveled to many diverse Native nations from Canada to Georgia, calling for unification, resistance, and the restoration of sacred power.

Tecumseh and Tenskwatawa's confederacy was the culmination of many movements that swept through Indigenous Northward America during the eighteenth century. An earlier coalition fought in Pontiac'due south War. Neolin, the Delaware prophet, influenced Pontiac, an Ottawa (Odawa) war principal, with his vision of Native independence, cultural renewal, and religious revitalization. Through Neolin, the Master of Life—the Great Spirit—urged Native peoples to shrug off their dependency on European appurtenances and technologies, reassert their faith in Native spirituality and rituals, and cooperate with ane some other against the "White people's ways and nature."xix Additionally, Neolin advocated violence against British encroachments on Native American lands, which escalated after the Seven Years' War. His message was peculiarly effective in the Ohio and Upper Susquehanna Valleys, where polyglot communities of Ethnic refugees and migrants from across eastern N America lived together. When combined with the militant leadership of Pontiac, who took up Neolin's bulletin, the many Native peoples of the region united in attacks against British forts and people. From 1763 until 1765, the Neat Lakes, Ohio Valley, and Upper Susquehanna Valley areas were embroiled in a war betwixt Pontiac's confederacy and the British Empire, a state of war that ultimately forced the English language to restructure how they managed Native-British relations and trade.

In the interim between 1765 and 1811, other Native prophets kept Neolin'southward message alive while encouraging Indigenous peoples to resist Euro-American encroachments. These individuals included the Ottawa leader "the Trout," besides chosen Maya-Ga-Wy; Joseph Brant of the Iroquois (Haudenosaunee); the Creek headman Mad Dog; Painted Pole of the Shawnee; a Mohawk adult female named Coocoochee; Primary Poc of the Potawatomi; and the Seneca prophet Handsome Lake. Again, the epicenter of this resistance and revitalization originated in the Ohio Valley and Bully Lakes regions, where from 1791 to 1795 a articulation force of Shawnee, Delaware, Miami, Iroquois, Ojibwe, Ottawa, Huron, Potawatomi, Mingo, Chickamauga, and other Indigenous peoples waged war against the American commonwealth. Although this "Western Confederacy" ultimately suffered defeat at the Boxing of Fallen Timbers in 1794, this Native coalition accomplished a number of armed forces victories against the commonwealth, including the destruction of two American armies, forcing President Washington to reformulate federal policy. Tecumseh's experiences as a warrior against the American military in this conflict probably influenced his later efforts to generate solidarity among Due north American Indigenous communities.

Tecumseh and Tenskwatawa articulated ideas and beliefs similar to their eighteenth-century predecessors. In item, Tenskwatawa pronounced that the Master of Life entrusted him and Tecumseh with the responsibility for returning Native peoples to the one true path and to rid Native communities of the dangerous and corrupting influences of Euro-American trade and culture. Tenskwatawa stressed the need for cultural and religious renewal, which coincided with his blending of the tenets, traditions, and rituals of Indigenous religions and Christianity. In particular, Tenskwatawa emphasized apocalyptic visions that he and his followers would usher in a new world and restore Native power to the continent. For Native peoples who gravitated to the Shawnee brothers, this accent on cultural and religious revitalization was empowering and spiritually liberating, peculiarly given the continuous American assaults on Native land and ability in the early on nineteenth century.

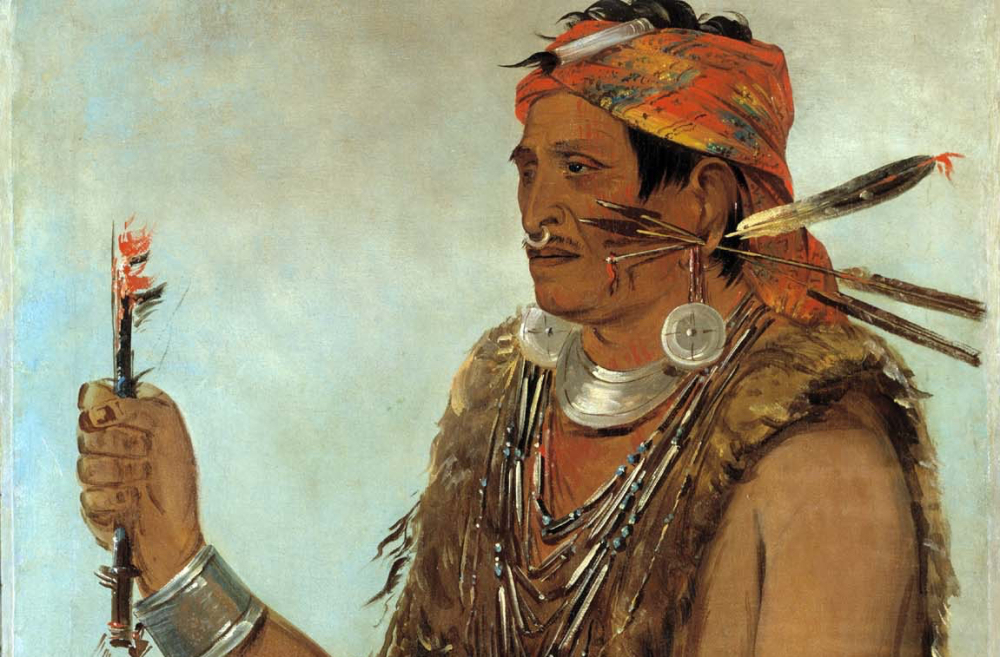

Tenskwatawa equally painted by George Catlin, in 1831. Caitlin acknowledged the prophet's spiritual power and painted him with a medicine stick. Wikimedia.

Tecumseh's confederacy drew heavily from Indigenous communities in the Erstwhile Northwest and the festering hatred for land-hungry Americans. Tecumseh attracted a wealth of allies in his adamant refusal to concede whatever more than land. Tecumseh proclaimed that the Master of Life tasked him with the responsibility of returning Native lands to their rightful owners. In his efforts to promote unity among Native peoples, Tecumseh also offered these communities a distinctly Native American identity that brought disparate Native peoples together under the banner of a common spirituality, together resisting an oppressive force. In brusk, spirituality tied together the resistance movement. Tecumseh and Tenskwatawa were not to a higher place using this unifying rhetoric to legitimate their ain potency inside Ethnic communities at the expense of other Native leaders. This manifested most visibly during Tenskwatawa's witch hunts of the 1800s. Those who opposed Tenskwatawa or sought to suit Americans were labeled witches.

While Tecumseh attracted Native peoples from around the Northwest, the Red Stick Creeks brought these ideas to the Southeast. Led past the Creek prophet Hillis Hadjo, who accompanied Tecumseh when he toured throughout the Southeast in 1811, the Red Sticks integrated certain religious tenets from the n and invented new religious practices specific to the Creeks, all the while communicating and analogous with Tecumseh after he left Creek Country. In doing so, the Cherry-red Sticks joined Tecumseh in his resistance movement while seeking to purge Creek gild of its Euro-American dependencies. Creek leaders who maintained relationships with the United States, in contrast, believed that accommodation and diplomacy might stave off American encroachments amend than violence.

Additionally, the Red Sticks discovered that most southeastern Indigenous leaders cared little for Tecumseh'southward confederacy. This lack of allies hindered the spread of a movement in the southeast, and the Red Sticks soon establish themselves in a ceremonious war against other Creeks. Tecumseh thus found footling support in the Southeast across the Ruddy Sticks, who by 1813 were cut off from the Due north by Andrew Jackson. Soon thereafter, Jackson's forces were joined past Lower Creek and Cherokee forces that helped defeat the Ruby-red Sticks, culminating in Jackson's victory at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend. Post-obit their defeat, the Red Sticks were forced to cede an unprecedented fourteen 1000000 acres of land in the Treaty of Fort Jackson. As historian Adam Rothman argues, the defeat of the Cherry-red Sticks allowed the United states to expand west of the Mississippi, guaranteeing the continued existence and profitability of slavery.twenty

Many Native leaders refused to join Tecumseh and instead maintained their loyalties to the American republic. Afterwards the failures of Native American unity and loss at the Battle of Tippecanoe in 1811, Tecumseh's confederation floundered. The State of war of 1812 between the Usa and Britain offered new opportunities for Tecumseh and his followers.21 With the The states distracted, Tecumseh and his confederated army seized several American forts on their own initiative. Eventually Tecumseh solicited British assist afterwards sustaining heavy losses from American fighters at Fort Wayne and Fort Harrison. Even and so, the confederacy faced an uphill boxing, particularly subsequently American naval forces secured command of the Cracking Lakes in September 1813, forcing British ships and reinforcements to retreat. Yet Tecumseh and his Native allies fought on despite being surrounded by American forces. Tecumseh told the British commander Henry Proctor, "Our lives are in the hands of the Slap-up Spirit. Nosotros are adamant to defend our lands, and if information technology is his volition, we wish to leave our basic upon them."22 Not soon thereafter, Tecumseh fell on the battlefields of Moraviantown, Ontario, in Oct 1813. His death dealt a severe blow to Native American resistance confronting the United States. Men like Tecumseh and Pontiac, however, left behind a legacy of Native American unity that was not presently forgotten.

VI. The War of 1812

Soon after Jefferson retired from the presidency in 1808, Congress ended the embargo and the British relaxed their policies toward American ships. Despite the embargo's unpopularity, Jefferson withal believed that more fourth dimension would have proven that peaceable coercion worked. Even so war with Uk loomed—a war that would galvanize the young American nation.

The War of 1812 stemmed from American entanglement in two distinct sets of international issues. The first had to exercise with the nation'south want to maintain its position as a neutral trading nation during the serial of Anglo-French wars, which began in the aftermath of the French Revolution in 1793. The second had older roots in the colonial and Revolutionary era. In both cases, American interests conflicted with those of the British Empire. British leaders showed little interest in accommodating the Americans.

Impressments, the exercise of forcing American sailors to join the British Navy, was among the most important sources of disharmonize between the two nations. Driven in office past trade with Europe, the American economy grew chop-chop during the kickoff decade of the nineteenth century, creating a labor shortage in the American shipping manufacture. In response, pay rates for sailors increased and American captains recruited heavily from the ranks of British sailors. As a outcome, around 30 percent of sailors employed on American merchant ships were British. As a commonwealth, the Americans advanced the notion that people could become citizens by renouncing their allegiance to their home nation. To the British, a person built-in in the British Empire was a subject area of that empire for life, a status they could not change. The British Navy was embroiled in a difficult state of war and was unwilling to lose any of its labor force. In order to regain lost crewmen, the British often boarded American ships to reclaim their sailors. Of course, many American sailors found themselves caught upwards in these sweeps and "impressed" into the service of the British Navy. Between 1803 and 1812, some six thousand Americans suffered this fate. The British would release Americans who could prove their identity, but this process could accept years while the sailor endured harsh conditions and the dangers of the Regal Navy.

In 1806, responding to a French proclamation of a complete naval blockade of Bully Britain, the British demanded that neutral ships first comport their appurtenances to United kingdom to pay a transit duty earlier they could keep to France. Despite loopholes in these policies between 1807 and 1812, Britain, French republic, and their allies seized about ix hundred American ships, prompting a swift and angry American response. Jefferson's embargo sent the nation into a deep depression and drove exports down from $108 million in 1807 to $22 million in 1808, all while having little effect on Europeans.23 Within 15 months Congress repealed the Embargo Deed, replacing it with smaller restrictions on merchandise with Britain and French republic. Although efforts to stand against Cracking U.k. had failed, resentment of British trade policy remained widespread.

Far from the Atlantic Ocean on the American frontier, Americans were also at odds with the British Empire. From their position in Canada, the British maintained relations with Native Americans in the Old Northwest, supplying them with goods and weapons in attempts to maintain ties in case of another state of war with the U.s.. The threat of a Native insurgence increased after 1805 when Tenskwatawa and Tecumseh built their brotherhood. The territorial governor of Illinois, William Henry Harrison, eventually convinced the Madison administration to allow for military activeness against the Native Americans in the Ohio Valley. The resulting Boxing of Tippecanoe drove the followers of the Prophet from their gathering place but did little to change the dynamics of the region. British efforts to arm and supply Native Americans, notwithstanding, angered Americans and strengthened anti-British sentiments.

Republicans began to talk of war as a solution to these issues, arguing that it was necessary to complete the War for Independence past preventing British efforts to go along America subjugated at sea and on land. The war would also stand for another battle against the Loyalists, some xxx-eight m of whom had populated Upper Canada afterward the Revolution and sought to establish a counter to the radical experiment of the Usa.24

In 1812, the Democratic-Republicans held 75 percent of the seats in the House and 82 percentage of the Senate, giving them a gratuitous hand to prepare national policy. Amidst them were the "State of war Hawks," whom i historian describes equally "as well immature to remember the horrors of the American Revolution" and thus "willing to risk another British war to vindicate the nation's rights and independence."25 This group included men who would remain influential long later the State of war of 1812, such as Henry Clay of Kentucky and John C. Calhoun of South Carolina.

Convinced past the State of war Hawks in his political party, Madison drafted a argument of the nation'southward disputes with the British and asked Congress for a war declaration on June 1, 1812. The Democratic-Republicans hoped that an invasion of Canada might remove the British from their backyard and forcefulness the empire to change their naval policies. After much negotiation in Congress over the details of the bill, Madison signed a declaration of war on June 18, 1812. For the second time, the United states was at war with U.k..

While the War of 1812 contained two key players—the United states and Great Britain—it also drew in other groups, such as Tecumseh and his Confederacy. The war tin can exist organized into three stages or theaters. The start, the Atlantic Theater, lasted until the spring of 1813. During this fourth dimension, Great Britain was chiefly occupied in Europe confronting Napoleon, and the United States invaded Canada and sent their fledgling navy against British ships. During the 2d stage, from early 1813 to 1814, the United States launched their 2d offensive against Canada and the Great Lakes. In this flow, the Americans won their get-go successes. The third stage, the Southern Theater, ended with Andrew Jackson'south January 1815 victory outside New Orleans, Louisiana.

During the war, the Americans were greatly interested in Canada and the Great Lakes borderlands. In July 1812, the U.s. launched their outset offensive against Canada. Past August, notwithstanding, the British and their allies rebuffed the Americans, costing the U.s. control over Detroit and parts of the Michigan Territory. Past the close of 1813, the Americans recaptured Detroit, shattered the Confederacy, killed Tecumseh, and eliminated the British threat in that theater. Despite these accomplishments, the American land forces proved outmatched by their adversaries.

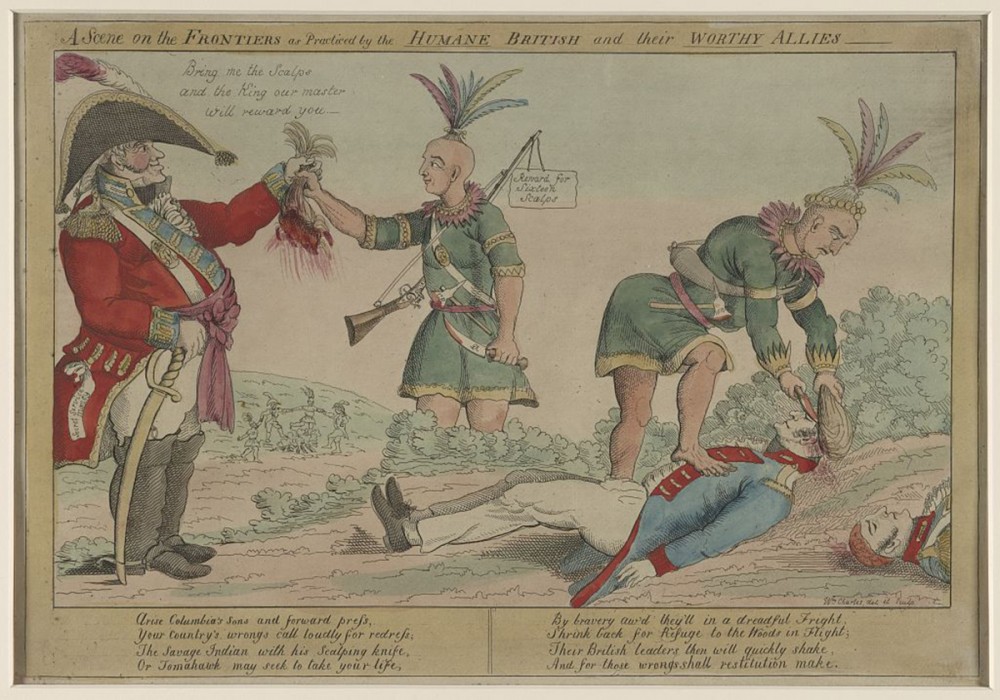

As pictured in this 1812 political cartoon published in Philadelphia, Americans lambasted the British and their native allies for what they considered "brutal" offenses during war, though Americans too were engaging in similar acts. William Charles, A scene on the frontiers as expert past the "humane" British and their "worthy" allies, Philadelphia, 1812. Library of Congress.

After the land campaign of 1812 failed to secure America's war aims, Americans turned to the baby navy in 1813. Privateers and the U.S. Navy rallied behind the slogan "Free Trade and Sailors' Rights!" Although the British possessed the most powerful navy in the earth, surprisingly the young American navy extracted early victories with larger, more heavily armed ships. By 1814, even so, the major naval battles had been fought with little effect on the state of war'southward effect.

With Britain'due south primary naval fleet fighting in the Napoleonic Wars, smaller ships and armaments stationed in North America were generally no match for their American counterparts. Early on, Americans humiliated the British in single ship battles. In retaliation, Captain Philip Bankrupt of the HMS Shannon attacked the USS Chesapeake, captained by James Lawrence, on June 1, 1813. Within vi minutes, the Chesapeake was destroyed and Lawrence mortally wounded. Yet the Americans did non give up. Lawrence commanded them, "Tell the men to burn faster! Don't give up the ship!"26 Lawrence died of his wounds iii days later, and although the Shannon defeated the Chesapeake, Lawrence's words became a rallying cry for the Americans.

Two and a half months later the USS Constitution squared off with the HMS Guerriere. As the Guerriere tried to outmaneuver the Americans, the Constitution pulled along broadside and began hammering the British frigate. The Guerriere returned fire, but as one sailor observed, the cannonballs just bounced off the Constitution'due south thick hull. "Huzzah! Her sides are made of fe!" shouted the sailor, and henceforth, the Constitution became known every bit "Old Ironsides." In less than thirty-five minutes, the Guerriere was so badly damaged that it was ready aflame rather than taken equally a prize.

In 1814, Americans gained naval victories on Lake Champlain near Plattsburgh, preventing a British land invasion of the Us and on the Chesapeake Bay at Fort McHenry in Baltimore. Fort McHenry repelled the nineteen-ship British fleet, enduring 20-seven hours of bombardment nigh unscathed. Watching from aboard a British ship, American poet Francis Scott Fundamental penned the verses of what would go the national anthem, "The Star Spangled Banner."

Impressive though these accomplishments were, they belied what was actually a poorly executed military campaign against the British. The U.S. Navy won their well-nigh significant victories in the Atlantic Sea in 1813. Napoleon's defeat in early on 1814, yet, immune the British to focus on Northward America and blockade American ports. Thanks to the blockade, the British were able to fire Washington, D.C., on August 24, 1814 and open a new theater of operations in the South. The British sailed for New Orleans, where they achieved a naval victory at Lake Borgne before losing the land invasion to Major Full general Andrew Jackson's troops in January 1815. This American victory actually came subsequently the United states and the United kingdom signed the Treaty of Ghent on December 24, 1814, merely the Battle of New Orleans proved to be a psychological victory that boosted American morale and affected how the war has been remembered.

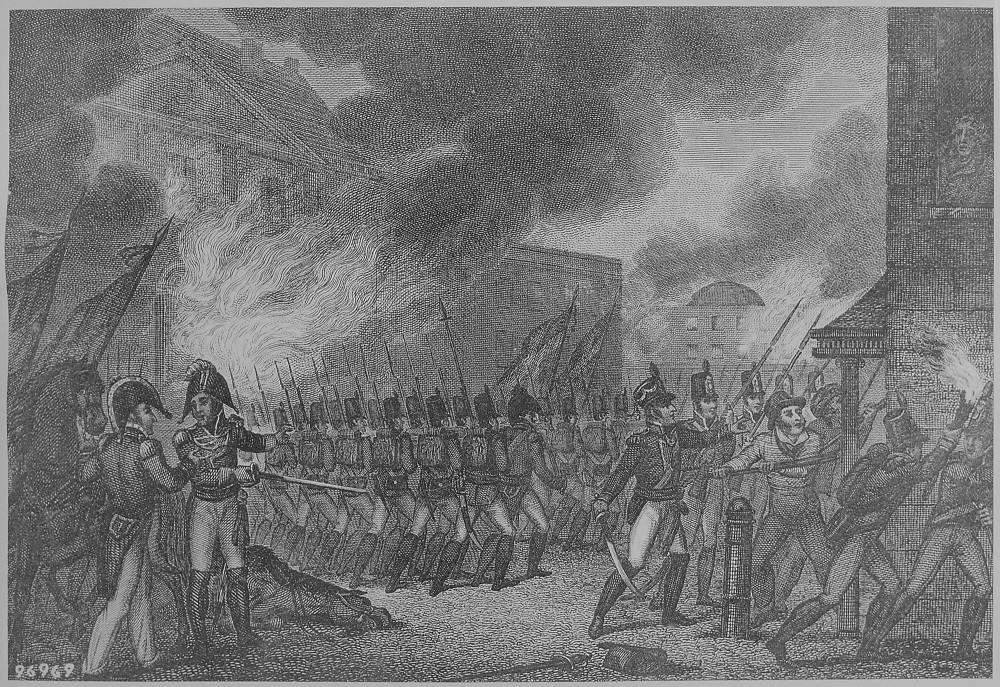

The artist shows Washington D.C. engulfed in flames every bit the British troops ready burn to the city in 1813. "Capture of the City of Washington," August 1814. Wikimedia.

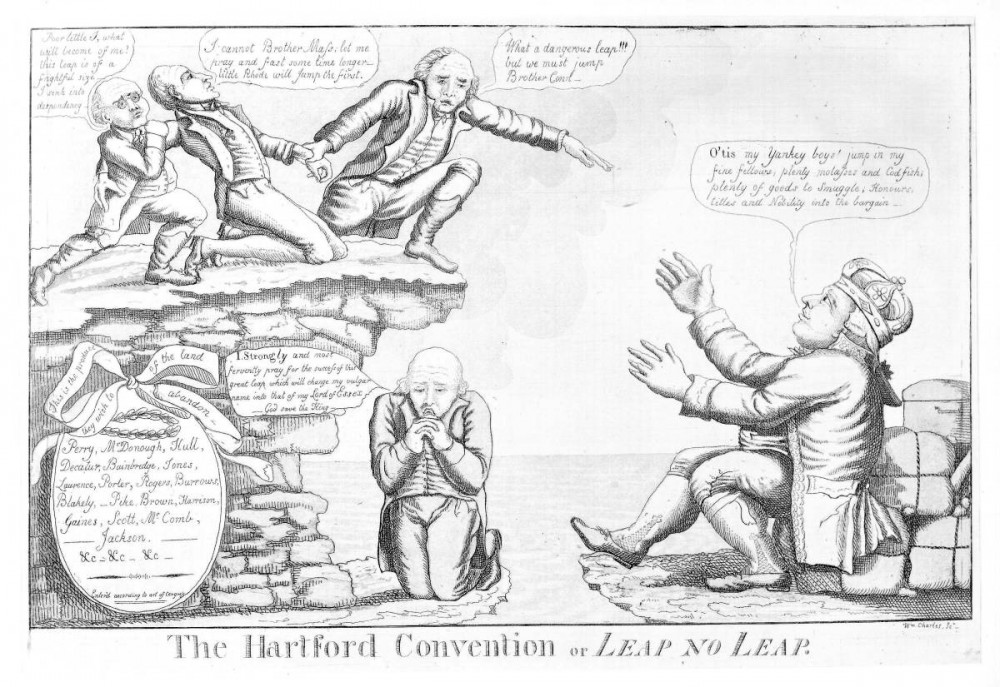

Only non all Americans supported the war. In 1814, New England Federalists met in Hartford, Connecticut, to try to end the war and curb the power of the Autonomous-Republican Party. They produced a document that proposed abolishing the 3-fifths rule that afforded southern enslavers disproportionate representation in Congress, limiting the president to a single term in office, and nearly importantly, enervating a ii-thirds congressional majority, rather than a uncomplicated majority, for legislation that declared war, admitted new states into the Union, or regulated commerce. With the 2-thirds majority, New England's Federalist politicians believed they could limit the power of their political foes.

Contemplating the possibility of secession over the War of 1812 (fueled in large function by the economic interests of New England merchants), the Hartford Convention posed the possibility of disaster for the still-immature U.s.. England, represented by the effigy John Bull on the correct side, is shown in this political cartoon with arms open up to accept New England back into its empire. William Charles Jr., The Hartford Convention or Bound No Leap. Wikimedia.

These proposals were sent to Washington, but unfortunately for the Federalists, the victory at New Orleans buoyed popular support for the Madison administration. With little evidence, newspapers accused the Hartford Convention'southward delegates of plotting secession. The episode demonstrated the waning power of Federalism and the need for the region'southward politicians to shed their aristocratic and Anglophile image. The next New England politician to presume the presidency, John Quincy Adams, would, in 1824, emerge not from within the Federalist fold but having served equally secretarial assistant of land nether President James Monroe, the leader of the Virginia Democratic-Republicans.

The Treaty of Ghent substantially returned relations between the Usa and Britain to their prewar status. The war, yet, mattered politically and strengthened American nationalism. During the war, Americans read patriotic paper stories, sang patriotic songs, and bought consumer goods decorated with national emblems. They also heard stories nigh how the British and their Native allies threatened to bring violence into American homes. For examples, rumors spread that British officers promised rewards of "beauty and booty" for their soldiers when they attacked New Orleans.27 In the Great Lakes borderlands, wartime propaganda fueled Americans' fear of Uk's Native American allies, whom they believed would slaughter men, women, and children indiscriminately. Terror and dearest worked together to make American citizens experience a stronger bond with their country. Because the war mostly cut off America'south merchandise with Europe, it also encouraged Americans to see themselves as different and separate; information technology fostered a sense that the country had been reborn.

Former treasury secretary Albert Gallatin claimed that the War of 1812 revived "national feelings" that had dwindled after the Revolution. "The people," he wrote, were now "more American; they experience and human activity more like a nation."28 Politicians proposed measures to reinforce the fragile Marriage through capitalism and built on these sentiments of nationalism. The United States continued to aggrandize into Native American territories with due west settlement in far-flung new states similar Tennessee, Ohio, Mississippi, and Illinois. Betwixt 1810 and 1830, the country added more than six k new post offices.

In 1817, South Carolina congressman John C. Calhoun called for edifice projects to "demark the commonwealth together with a perfect system of roads and canals."29 He joined with other politicians, such as Kentucky'due south powerful Henry Clay, to promote what came to be called an American Organization. They aimed to brand America economically independent and encouraged commerce betwixt the states over trade with Europe and the West Indies. The American System would include a new Bank of the United States to provide uppercase; a high protective tariff, which would heighten the prices of imported goods and help American-fabricated products compete; and a network of "internal improvements," roads and canals to permit people take American goods to market place.

These projects were controversial. Many people believed that they were unconstitutional or would increase the federal government'south power at the expense of the states. Even Calhoun later inverse his mind and joined the opposition. The War of 1812, however, had reinforced Americans' sense of the nation's importance in their political and economic life. Even when the federal government did not deed, states created banks, roads, and canals of their own.

What may have been the boldest declaration of America's postwar pride came in 1823. President James Monroe issued an ultimatum to the empires of Europe in order to support several wars of independence in Latin America. The Monroe Doctrine declared that the United states considered its unabridged hemisphere, both North and Due south America, off-limits to new European colonization. Although Monroe was a Jeffersonian, some of his principles echoed Federalist policies. Whereas Jefferson cut the size of the military and ended all internal taxes in his first term, Monroe advocated the need for a strong military machine and an aggressive foreign policy. Since Americans were spreading out over the continent, Monroe authorized the federal authorities to invest in canals and roads, which he said would "shorten distances and, by making each office more accessible to and dependent on the other . . . shall bind the Union more closely together."30 As Federalists had attempted 2 decades before, Autonomous-Republican leaders after the War of 1812 advocated strengthening the regime to strengthen the nation.

Vii. Conclusion

Monroe's election later on the conclusion of the War of 1812 signaled the decease knell of the Federalists. Some predicted an "era of expert feelings" and an cease to party divisions. The State of war had cultivated a profound sense of union among a diverse and divided people. However that "era of practiced feelings" would never really come. Political division continued. Though the dying Federalists would fade from political relevance, a schism within the Democratic-Republican Party would requite rise to Jacksonian Democrats. Political limits connected along class, gender, and racial and ethnic lines. At the same fourth dimension, industrialization and the development of American capitalism required new justifications of inequality. Social change and increased immigration prompted nativist reactions that would divide "true" Americans from dangerous or undeserving "others." Still, a cacophony of voices clamored to be heard and struggled to realize a social order compatible with the ideals of equality and individual liberty. As always, the meaning of commonwealth was in flux.

VIII. Primary Sources

1. Letter of Cato and petition by "the negroes who obtained liberty past the tardily act," inPostscript to the Freeman's Journal, September 21, 1781

The elimination of slavery in northern states like Pennsylvania was ho-hum and hard-fought. A beak passed in 1780 began the slow process of eroding slavery in the country, but a proposal merely ane year later would have erased that bill and furthered the altitude between slavery and freedom. The activeness of Black Philadelphians and others succeeded in defeating this measure. In this letter to the Blackness paper,Philadelphia Liberty's Journal, a formerly enslaved human uses the rhetoric of the American Revolution to attack American slavery.

two. Thomas Jefferson's racism, 1788

American racism spread during the kickoff decades afterward the American Revolution. Racial prejudice existed for centuries, merely the conventionalities that African-descended peoples were inherently and permanently inferior to Anglo-descended peoples developed old effectually the late eighteenth century. Writings such as this piece from Thomas Jefferson fostered faulty scientific reasoning to justify laws that protected slavery and white supremacy.

3. Black scientist Benjamin Banneker demonstrates Black intelligence to Thomas Jefferson, 1791

Benjamin Banneker, a free Black American and largely cocky-taught astronomer and mathematician, wrote Thomas Jefferson, then Secretary of State, on August 19, 1791. Banneker included this letter, as well as Jefferson's brusk reply, in several of the get-go editions of his almanacs in part considering he hoped it would dispel the widespread assumption that Jefferson perpetuated in his Notes on the Land of Virginia that Black people were incapable of intellectual accomplishment.

4. Creek headman Alexander McGillivray (Hoboi-Hili-Miko) seeks to build an alliance with Espana, 1785

Native peoples had long employed strategies of playing Europeans off confronting each other to maintain their independence and neutrality. As early on as 1785, the Creek headman Alexander McGillivray (Hoboi-Hili-Miko) saw the threat the expansionist Americans placed on Native peoples and the inability of a weak United States government to restrain their citizens from encroaching on Native lands. McGillivray sought the assist and protection of the Spanish in guild to maintain the supply of merchandise goods into Creek land and counter the Americans.

five. Tecumseh Calls for Native American resistance, 1810

Like Pontiac before him, Tecumseh articulated a spiritual message of Native American unity and resistance. In this certificate, he acknowledges his Shawnee heritage, simply appeals to a larger customs of "red men," who he describes every bit "once a happy race, since made miserable past the white people." This certificate reveals not only Tecumseh'southward bulletin of resistance, but it also shows that Anglo-American understandings of race had spread to Native Americans as well.

half-dozen. Congress debates going to war, 1811

Americans were not united in their support for the War of 1812. In these two documents we hear from members of congress as they debate whether or not America should go to war against Uk.

7. Abigail Bailey escapes an calumniating relationship, 1815

Women in early America suffered from a lack of rights or means of defending themselves confronting domestic corruption. The example of Abigail Bailey is remarkable because she was able to successfully free herself and her children from an calumniating husband and begetter.

viii. Genius of the Ladies magazine illustration, 1792

Despite the restrictions imposed on their American citizenship, white women worked to expand their rights to education in the new nation using literature and the arts. The first journal for women in the United States,The Lady'southward Magazine, and repository of entertaining knowledge, introduced their initial volume with an engraving jubilant the transatlantic exchange between women'south rights advocates. In the engraving, English writer Mary Wollstonecraft presents her work, "A Vindication of the Rights of Woman," to Liberty who has the tools of the arts at her feet.

ix. America Guided past Wisdom engraving, 1815

This engraving reflects the sense of triumph many white Americans felt following the War of 1812. Drawing from the visual language of Jeffersonian Republicans, we see America—represented as a woman in classical dress—surrounded by gods of wisdom, commerce, and agriculture on one side and a statue of George Washington emblazoned with the recent state of war's victories on the other. The romantic sense of the United States as the heir to the ancient Roman democracy, pride in military victory, and the glorification of domestic product contributed to the idea the young nation was near to enter an "era of expert feelings."

IX. Reference Material

This affiliate was edited by Nathaniel C. Green, with content contributions by Justin Clark, Adam Costanzo, Stephanie Gamble, Dale Kretz, Julie Richter, Bryan Rindfleisch, Angela Riotto, James Risk, Cara Rogers, Jonathan Wilfred Wilson, and Charlton Yingling.

Recommended citation: Justin Clark et al., "The Early on Republic," Nathaniel C. Green, ed., in The American Yawp, eds. Joseph Locke and Ben Wright (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2018).

Recommended Reading

- Appleby, Joyce. Liberalism and Republicanism in the Historical Imagination. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 1992.

- Bailey, Jeremy D. Thomas Jefferson and Executive Power. Cambridge, United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland: Cambridge University Printing, 2010.

- Blackhawk, Ned. Violence over the Land: Indians and Empires in the Early American W. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Printing, 2008.

- Bradburn, Douglas. The Citizenship Revolution: Politics and the Cosmos of the American Union, 1774–1804. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Printing, 2009.

- Cleves, Rachel Hope. The Reign of Terror in America: Visions of Violence from Anti-Jacobinism to Antislavery. New York: Cambridge Academy Press, 2009.

- Dubois, Laurent. Avengers of the New Globe: The Story of the Haitian Revolution. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2005.

- Edmunds, R. David. The Shawnee Prophet. Lincoln: Academy of Nebraska Press, 1983.

- Eustace, Nicole. 1812: War and the Passions of Patriotism. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Printing, 2012.

- Fabian, Ann. The Skull Collectors: Race, Science, and America's Unburied Dead. Chicago: University of Chicago Printing, 2010.

- Freeman, Joanne B. Affairs of Accolade: National Politics in the New Democracy. New Oasis, CT: Yale University Press, 2001.

- Furstenberg, François. In the Proper noun of the Begetter: Washington'due south Legacy, Slavery, and the Making of a Nation. New York: Penguin, 2006.

- Kastor, Peter J. The Nation'due south Crucible: The Louisiana Purchase and the Creation of America. New Oasis, CT: Yale University Press, 2004.

- Kelley, Mary. Learning to Stand up and Speak: Women, Education, and Public Life in America's Republic. Chapel Hill: University of N Carolina Printing, 2006.

- Kerber, Linda. Federalists in Dissent: Imagery and Credo in Jeffersonian America. Ithaca, NY: Cornell Academy Press, 1970.

- _________. Women of the Republic: Intellect and Ideology in Revolutionary America. Chapel Hill: Academy of North Carolina Press, 1997.

- Lewis, Jan. The Pursuit of Happiness: Family unit and Values in Jefferson's Virginia. New York: Cambridge Academy Printing, 1985.

- Manion, Jen. Liberty's Prisoners: Carceral Civilization in Early America. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2015.

- Onuf, Peter. Jefferson's Empire: The Linguistic communication of American Nationhood. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2000.

- Porterfield, Amanda. Conceived in Doubt: Faith and Politics in the New American Nation (Chicago: Academy of Chicago Press, 2012.

- Rothman, Adam. Slave State: American Expansion and the Origins of the Deep South. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2009.

- Rothman, Joshua D. Notorious in the Neighborhood: Sexual activity and Families Beyond the Color Line in Virginia, 1787–1861. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003.

- Sidbury, James. Ploughshares into Swords: Race, Rebellion, and Identity in Gabriel'southward Virginia, 1730–1810. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1997.

- Smith-Rosenberg, Carroll. This Tearing Empire: The Nascency of an American National Identity. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2012.

- Taylor, Alan. The Civil State of war of 1812: American Citizens, British Subjects, Irish Rebels, and Indian Allies. New York: Random House, 2010.

- Waldstreicher, David. In the Midst of Perpetual Fetes: The Making of American Nationalism 1776–1820. Chapel Colina: Academy of North Carolina Press, 1997.

Notes

Source: https://www.americanyawp.com/text/07-the-early-republic/

0 Response to "Loyalist Clip Art Battle of New Orleans in 1815 Clip Art"

Post a Comment